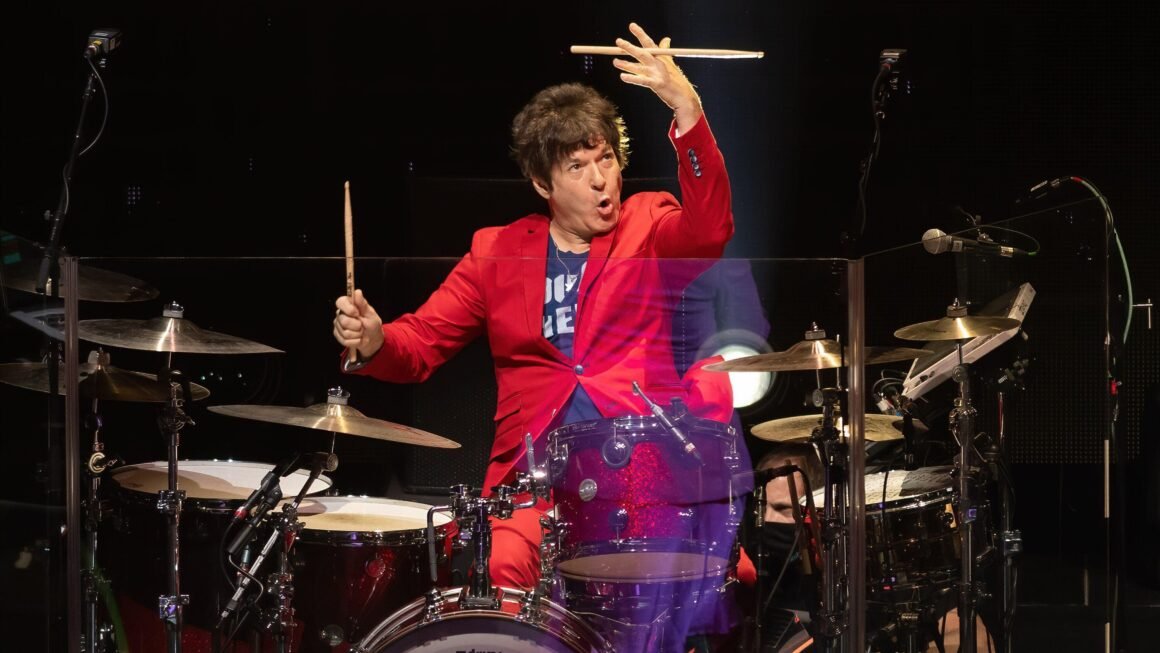

Clem Burke, the thunderous yet precise heartbeat of Blondie, didn’t just play the drums — he absorbed them. Over decades behind the kit, Burke built a drumming style that was uniquely his own, but at its core lay the influence of legends who taught him not just how to play, but why to play.

Perhaps his most deeply felt inspiration was Keith Moon, the frenetic drummer of The Who. Burke admired Moon’s raw power and boundless energy, and his own playing often reflected a controlled chaos: wild fills and explosive fills, but always tethered to a solid groove. When Moon died in 1978, Burke famously ended a Blondie set by kicking his drum kit into the crowd, shouting, “That’s for Keith Moon — the greatest drummer in the world!” This moment captured not just tribute, but genuine reverence.

Alongside Moon, Burke frequently cited Ringo Starr of The Beatles as another major influence. In interviews, he credited his time studying 1960s session drummers — including Ringo — as foundational. Burke even listed the 1963 album With the Beatles as an essential record for drummers, noting how Ringo’s feel on tracks like “This Boy” shaped his understanding of rhythm and space.

Burke was also deeply inspired by studio drummers from earlier eras — in particular, Hal Blaine and Earl Palmer. These were men who could play anything, from cinematic pop to gritty rock, and Burke admired their ability to serve the song rather than overshadow it. He once said he wanted his drumming to “contribute to the song rather than detract” — a credo drawn straight from his respect for Blaine and Palmer.

This wide palette of influences — from Moon’s wildness to Starr’s musicality, and Blaine and Palmer’s studio wisdom — became the backbone of Burke’s style. On tracks like “Dreaming” and “Atomic,” you can hear the blend: manic fills, strong time-keeping, and a willingness to experiment. His work on Blondie’s Parallel Lines album, for example, shows how he could channel both energetic punch and precise groove in a single take.

But Burke’s influences didn’t end with the drummers of rock’s golden age. In interviews, he also mentioned Kenney Jones (of The Small Faces and The Who) as a favorite, pointing out Jones’s tasteful grooves and melodic fills. For Burke, drumming wasn’t just about volume or speed — it was about feel, songcraft, and history.

His respect for these greats was more than admiration — it was a foundation for his identity. Burke’s approach to the drums showed a rare combination of power and nuance. Whether in a raucous live punk set or a polished studio recording, his playing carried the legacy of his heroes while pushing forward his own voice.

In honoring those drummers, Clem Burke became more than a beat keeper — he became a bridge. A bridge between the classic rock titans and the new wave energy of Blondie, between session precision and punk bravado. And in doing so, he didn’t just play the drums: he carried their spirit forward.