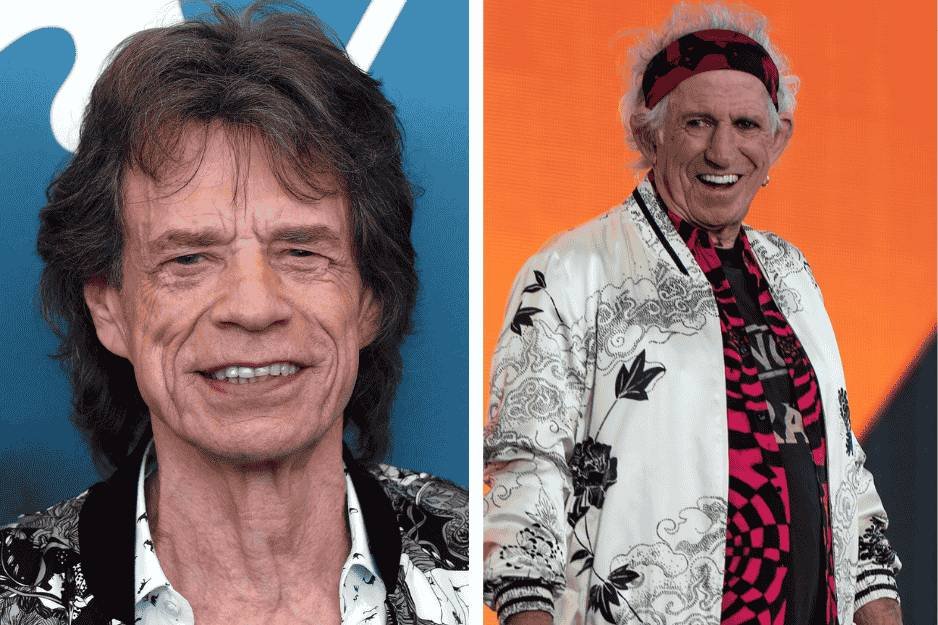

Creating one memorable record is a rare feat in itself, but The Rolling Stones built a career out of cranking out album after album of bluesy rock classics. Still, no matter how much success they enjoyed, guitarist Keith Richards didn’t see all their work with rose-colored glasses—especially as they transitioned into the 1980s. For Richards, frontman Mick Jagger’s push toward mainstream appeal started to steer the band off course, overshadowing the raw sound they were known for.

By the time they released Exile on Main St., The Stones had already secured their legacy as rock titans, even brushing off comparisons to The Beatles. But the industry around them was changing fast. Disco, punk, and hip-hop were entering the scene, and while the Stones had experimented with new genres, especially on songs like “Respectable” from Some Girls, Jagger was beginning to stray from the rock roots that defined them.

The early signs of this shift surfaced with Emotional Rescue, an album that leaned heavily into pop and disco sounds, much to the dismay of Richards. Though some standout songs made the cut, Richards felt many tracks on the record were not a fit for The Stones. Instead, he believed these were tunes better suited for other artists or even solo ventures by Jagger himself.

It didn’t stop there. As they moved through the decade, Undercover and Dirty Work came to define a low point in their career, loaded with what Richards considered The Stones’ most overproduced, style-driven work to date. The band’s bluesy grit seemed diluted, replaced by pop textures and pastel-colored outfits that felt like a hollow attempt to stay relevant. For Richards, the band’s original essence was slipping away, something he didn’t hesitate to chalk up to Jagger’s influence.

“Undercover of the Night, Emotional Rescue—these are all Mick’s calculations about the market,” Richards noted. “And they’re not the best records we’ve made. See, Mick listens to too much bad shit.”

In Richards’ eyes, Jagger’s attempts to stay hip or trendy were costing the band their authenticity.

The Stones’ redemption wouldn’t come until the 1990s, when they returned with Voodoo Lounge, an album that finally felt like a balanced collaboration between Jagger’s desire to experiment and Richards’ insistence on rock fundamentals. While later projects like “Might As Well Get Juiced” on Bridges to Babylon may not have been universally loved, Richards believed the album’s creative direction came from a genuine place, not a desperate bid for radio play.

Looking back, it’s easy to see why Richards doesn’t rank Emotional Rescue or Undercover alongside their timeless classics like Sticky Fingers. His critiques of those albums echo the words of John Lennon, who once famously claimed that Jagger merely “absorbs and copies what’s around him.” For Richards, it wasn’t the evolution of their sound that was the problem—it was the detour into chasing trends that almost led The Stones astray.