In rock and roll, the role of a bassist has always been a tricky one. Often relegated to the shadows, many have mistaken the bassist’s role as merely a “less talented guitarist.” However, legendary players like James Jamerson and John Entwistle redefined the bass as a lead instrument with its own voice, proving that the bottom end could drive a song in powerful ways. Even Paul McCartney, often celebrated for his melodic approach to bass in The Beatles, met his match when it came to George Harrison’s admiration for another bassist: Willy Weeks.

By the time The Beatles broke up, Harrison had his fill of McCartney’s domineering approach to the band’s creative process. While public attention largely focused on the feud between McCartney and John Lennon, Harrison felt equally stifled, often describing his frustration with how McCartney’s insistence on control stifled his own contributions.

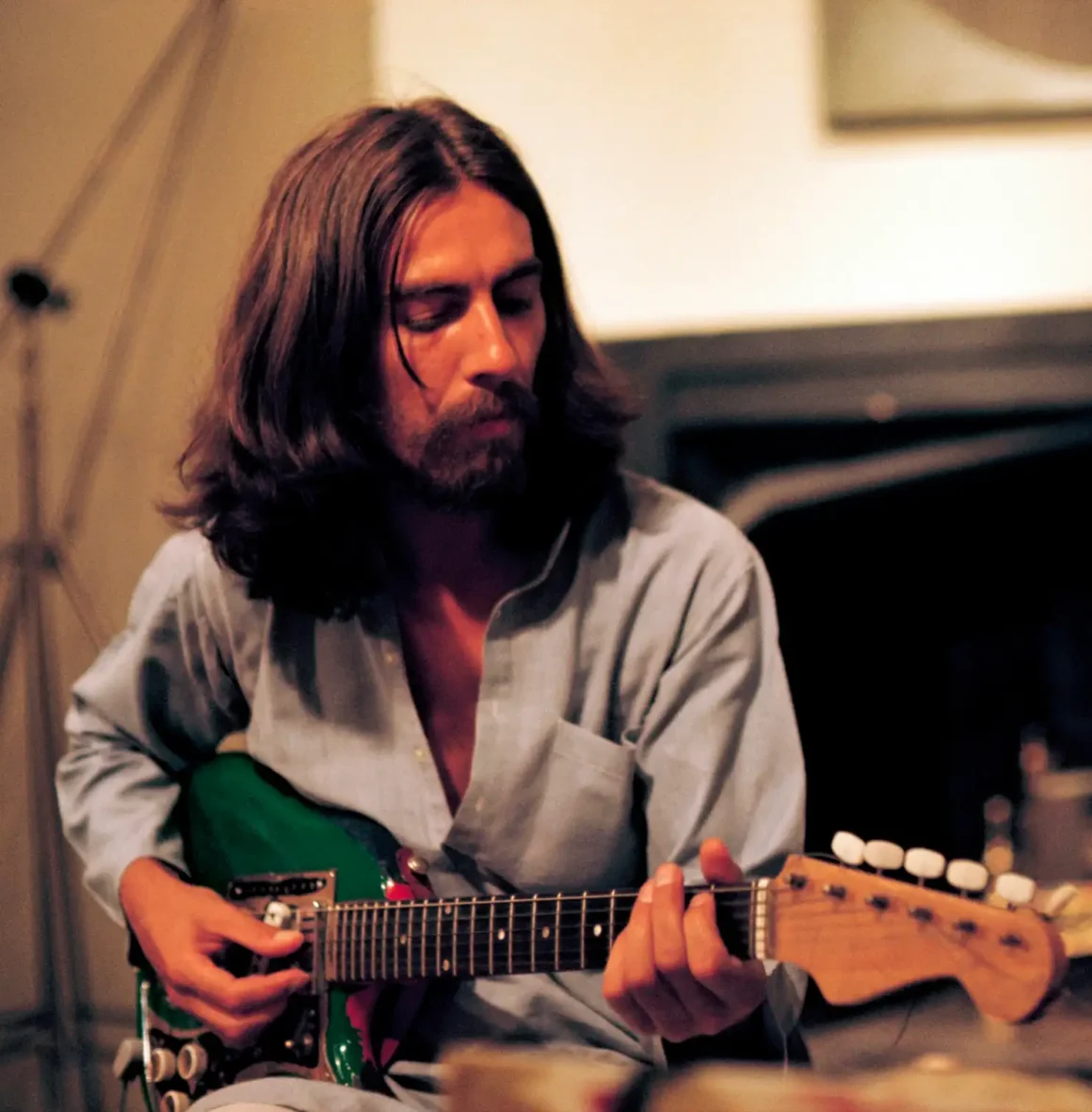

With newfound freedom in his solo career, Harrison carved a unique path, creating some of his most adventurous music yet. His landmark album All Things Must Pass showcased his expanded musical vision—from the heavy guitar riffs of “Let It Down” to the twangy, country-inspired “Behind That Locked Door.” This liberation allowed Harrison to explore styles and collaborate with artists in ways he never could within the constraints of The Beatles.

Enter Willy Weeks, a bassist whose soulful, expressive style aligned perfectly with Harrison’s musical exploration in the mid-1970s. Known for his work with icons like Donny Hathaway, Weeks brought a rhythmic bounce and sensitivity that Harrison found irresistible. Weeks’s groove-oriented approach was exactly what Harrison sought for his R&B-influenced sounds on Extra Texture and later projects. Though not widely celebrated, Weeks possessed an intuitive sense of timing and musicality, creating moments that grounded Harrison’s compositions with soul and depth.

Harrison couldn’t help but compare Weeks’s approach to McCartney’s, and in doing so, he acknowledged a deep appreciation for Weeks’s talent.

Reflecting on his sessions with Weeks, Harrison once admitted, “Even then, to play with The Beatles, I’d rather have Willy Weeks on bass than Paul McCartney. That’s the truth, with all respect to Paul. Being with The Beatles was like being in a box—it took years after leaving them to get to play with other musicians.”

Harrison’s respect for Weeks wasn’t just a matter of taste; it was rooted in his admiration for Weeks’s command of his instrument. Listening to Weeks’s performance on “Love Comes to Everyone” from Harrison’s 1979 self-titled album, it’s easy to understand the appeal. Weeks didn’t simply follow the beat; he played with a sense of balance and interplay, reacting to every nuance, just as Harrison had done on The Beatles’ early albums.

Weeks’s musicianship reminded Harrison of what true collaboration could achieve. On Hathaway’s live rendition of “Everything is Everything,” Weeks crafts a solo that echoes Harrison’s own minimalistic genius. Never overstaying his welcome, he adds just enough to make his presence felt without overwhelming the track—a skill Harrison greatly valued.

In the end, Willy Weeks remained one of the quiet geniuses in rock history, emblematic of the understated excellence that Harrison prized in his collaborators. While McCartney’s melodic basslines helped define The Beatles’ sound, it was Weeks’s subtle, soulful approach that gave Harrison the freedom to experiment as an artist. As Harrison once hinted, sometimes it’s the quiet players who leave the most lasting impression.