In March 1966, John Lennon, a member of the Beatles, made a comment that would ignite one of the most controversial moments in music history.

During an interview with Maureen Cleave for the London Evening Standard, Lennon casually stated, “We’re more popular than Jesus now.” This statement, though initially overlooked in England, would go on to create a global uproar, especially in the United States, leaving a lasting impact on the music world and the Beatles’ legacy.

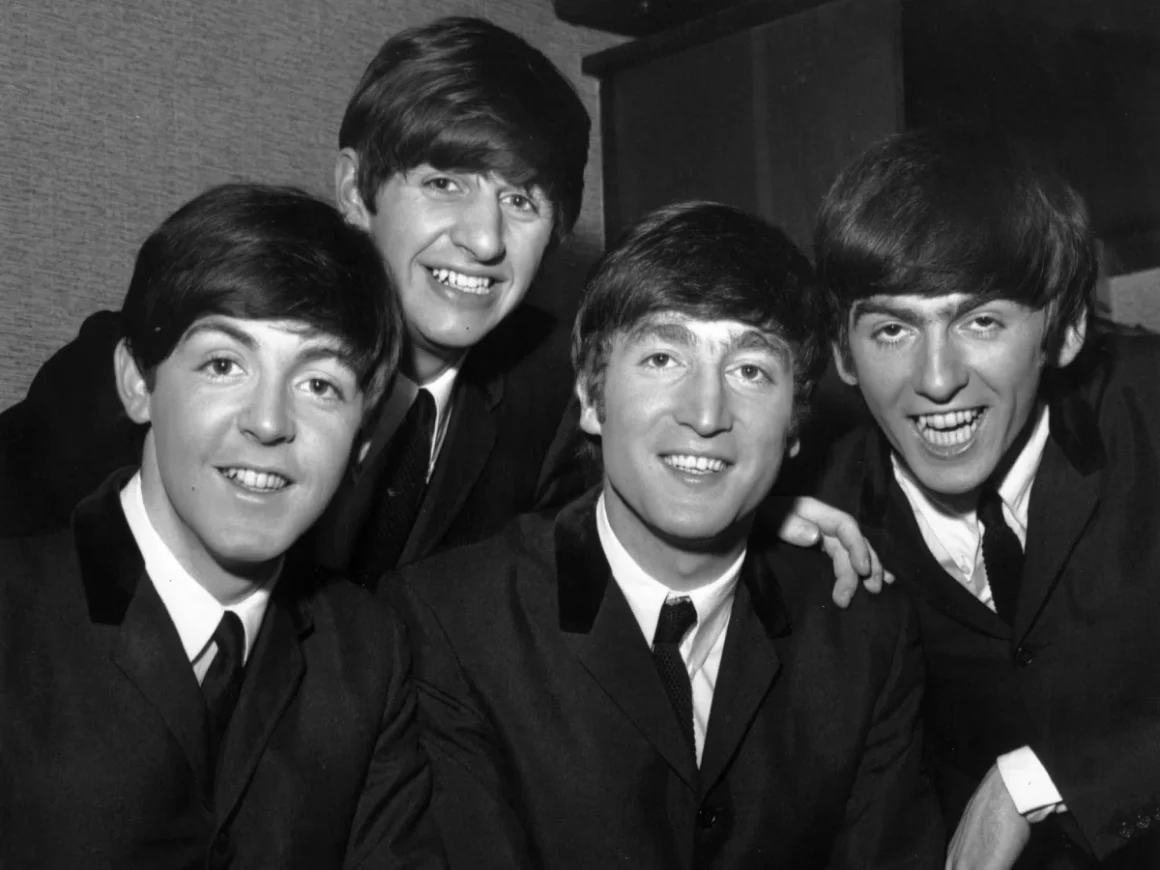

At the time, the Beatles were at the height of their fame. Cleave’s interview, part of a five-part series titled “How Does a Beatle Live?”, was meant to give fans a glimpse into the personal lives of the band members. The profile of Lennon, in particular, touched on various aspects of his life, including his strained relationship with his father and his growing interest in religion.

However, it was his remark about Christianity that would later dominate headlines.

Lennon’s full statement was more than just a provocative quip. He elaborated, “Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue about that; I’m right and I’ll be proved right. We’re more popular than Jesus now; I don’t know which will go first—rock ’n’ roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.”

At the time, this comment didn’t cause much of a stir in England, where the Church of England was often seen as outdated and disconnected from the younger generation.

The real controversy began months later when the interview was republished in the U.S. teen magazine Datebook in July 1966. This magazine, known for its political edge, brought Lennon’s words to the attention of a much broader and more conservative audience. The reaction was swift and intense, especially in the Southern United States, where the remark was seen as blasphemous.

Radio hosts Tommy Charles and Doug Layton from Birmingham, Alabama, were among the first to express their outrage, calling for a boycott of the Beatles. They refused to play the band’s music and initiated a “Ban the Beatles” campaign, which quickly gained traction across the country.

Other radio stations followed suit, with some even going as far as to organize public burnings of Beatles records. The South Carolina Ku Klux Klan also got involved, nailing the band’s records to a cross before setting it on fire—a dramatic and chilling response to what they viewed as an attack on Christianity.

As the controversy escalated, Lennon initially remained silent, while others, including Cleave and Beatles manager Brian Epstein, tried to defend him. Cleave clarified that Lennon wasn’t comparing the Beatles to Christ, but was instead commenting on the declining influence of Christianity. Epstein, concerned about the potential danger the band might face on their upcoming U.S. tour, even considered canceling it.

However, despite the uproar, none of the American venues chose to cancel the Beatles’ performances.

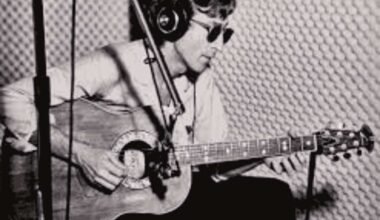

When the Beatles arrived in Chicago in August 1966, Lennon finally addressed the controversy in a press conference. He expressed regret, saying, “I never meant it to be a lousy anti-religious thing. I apologize if that will make you happy. I still don’t know quite what I’ve done. I’ve tried to tell you what I did do, but if you want me to apologize, if that will make you happy, then—okay, I’m sorry.” His apology, though somewhat reluctant, helped to quell much of the public outrage, but the incident left a mark on the band and their future.

The backlash they faced during the 1966 tour contributed to the Beatles’ decision to stop performing live and focus solely on studio work. The combination of the controversy and the exhaustion from years of relentless touring marked a turning point in the band’s career.

Looking back, the “more popular than Jesus” remark reflects a different era—one where celebrities were less guarded and more candid in their public statements. It was also a time when cultural and religious sensitivities varied greatly between regions, leading to vastly different interpretations of the same words.

In the end, while the controversy surrounding Lennon’s statement was intense, it also underscored the Beatles’ influence on popular culture. Their ability to provoke such a strong reaction highlighted just how significant they had become—not just as musicians, but as cultural icons who could challenge the status quo and spark global debates.

The incident remains a significant chapter in the history of music, illustrating the powerful intersection of fame, religion, and public opinion.