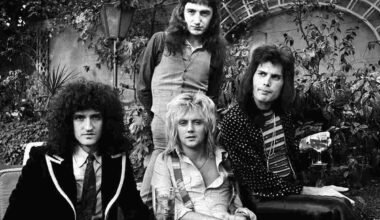

Some songs were never meant for the stage.

While fans dream of seeing their favorite tracks come to life in concert, the brutal truth is: not everything can translate from vinyl to venue. That’s something Roger Waters knew better than most. To him, the studio wasn’t just a recording space—it was a sonic canvas. And some of Pink Floyd’s finest work? It belonged there.

In a world where fans crave perfection from the stage, Pink Floyd thrived in chaos and experimentation. From Dark Side of the Moon to Wish You Were Here, they created sounds so rich and layered that live recreations were nearly impossible. Even with elaborate shows and hired choirs, like during their Pulse performance, there were always invisible hands—tape loops, triggers, and stage tech—that helped recreate the magic.

This wasn’t new for Pink Floyd. Even in their earliest days under Syd Barrett, songs like Interstellar Overdrive were wild beasts—different every night, impossible to tame or replicate. The idea of capturing that same energy live was almost laughable. Barrett didn’t mind. And Waters? He embraced it.

That mindset only grew stronger as the band evolved.

By the time they reached Echoes and A Saucerful of Secrets, live versions started to sound like entirely different pieces. Look no further than Live at Pompeii, where ambience reigned supreme and improvisation ruled. Waters wasn’t chasing replication—he was chasing reinvention.

And his inspiration? The Beatles.

Pink Floyd were stunned by Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, a record that shattered the idea that songs had to be playable live. Waters once said in 1967:

“We don’t think it’s dishonest because we can’t play live what we play on records. It’s a perfectly OK scene. Can you imagine somebody trying to play ‘A Day In The Life’? Yet that’s one of the greatest tracks ever made.”

To him, there was no shame in creating studio-bound masterpieces. If the music moved people, it didn’t matter if it could be played live—or ever performed at all.

That philosophy became gospel during the making of epics like Shine On You Crazy Diamond—tracks so layered and emotionally vast, they transcended performance. Could a single guitar replicate that ghostly intro? Maybe. But would it feel the same? Waters didn’t think so.

By the end of the 1970s, he had begun to drift from the adrenaline of live shows altogether. The crowds, the chaos—it wasn’t where his heart lived. His true love was the studio, where every echo and silence was under his control. A place where he could sculpt sound like clay.

And maybe that’s what made Pink Floyd different. They weren’t just performers. They were architects of emotion, builders of sonic worlds. Some of those worlds were never meant to be stepped into under stage lights.

They were built for your headphones. For your solitude. For your soul.