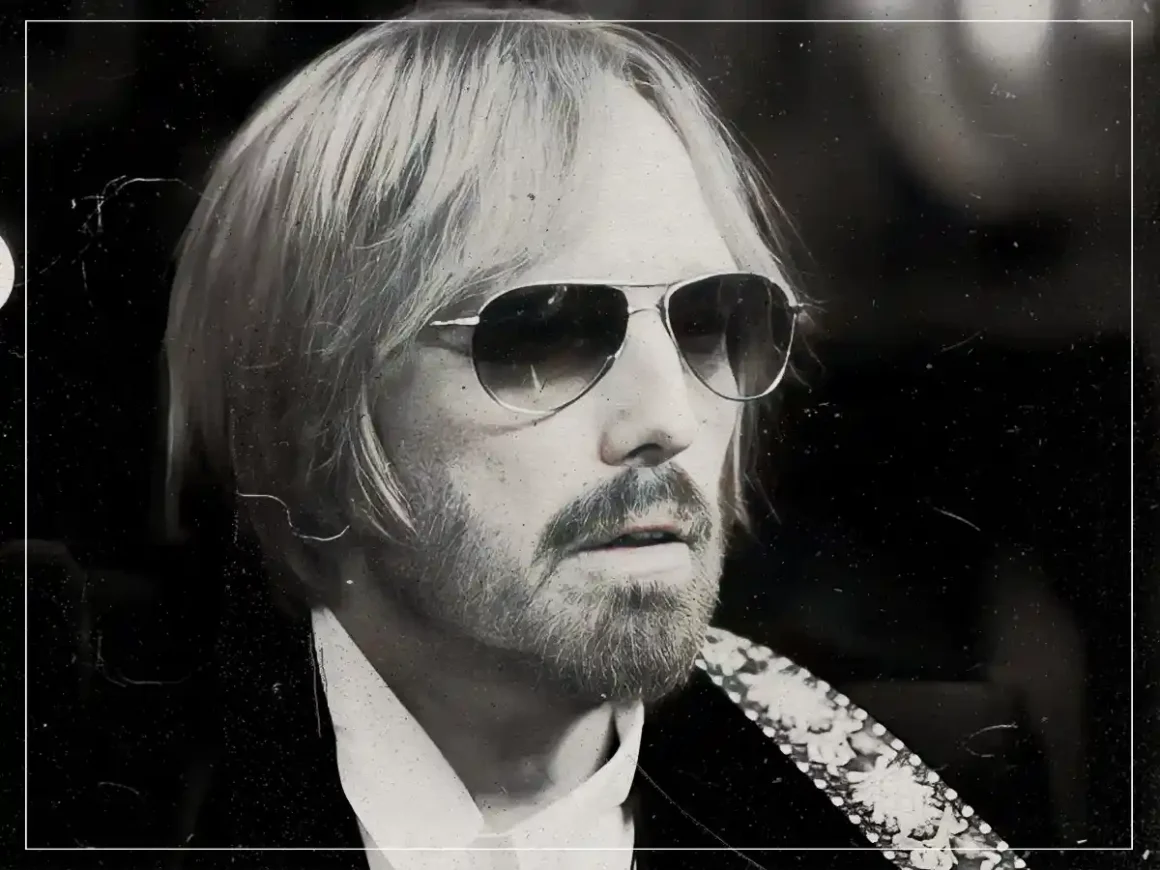

Tom Petty’s decision to fire longtime drummer Stan Lynch was far more than a personnel change — it marked a turning point in the history of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, a band once defined by deep friendships, shared musical chemistry and decades of collaborative success. What looked like an internal personnel shuffle was actually the end of an era for a group that had helped shape American rock.

From the beginning, Petty saw himself as part of a collective rather than the boss, even if fans knew the band by his name. That dynamic, though sincere on paper, created underlying tension — especially for Lynch, whose resentment over Petty’s frontman status was something that never fully healed.

The friction between Petty and Lynch wasn’t sudden so much as cumulative. By the time the Heartbreakers were recording Into the Great Wide Open in the early 1990s, Petty was already exploring solo-minded creative terrain. His work with producer Jeff Lynne and outside collaborators gave him new musical momentum, but it also created divisions within the group. Lynch later described the sessions as transactional — “Get in here, do your shit, get out of here” — a stark contrast to the collaborative vibe that had once defined the band.

While some bandmates seemed to shrug off Petty’s solo excursions, Lynch increasingly checked out mentally and emotionally — at one point reportedly feeling “like we were just playing someone else’s songs.” This frustrated Petty, who was pushing ahead with new ideas and expecting the band to pull in the same direction.

By the mid-1990s, Petty had decided to record his next major work — Wildflowers — with session drummer Steve Ferrone, a seasoned pro who could nail the grooves Petty was hearing in his head. That choice wasn’t merely practical; it symbolized a broader shift in musical vision that Lynch no longer fit.

Lynch perceived being left out of a project that was essentially still a Heartbreakers album as a personal slight, and the rift deepened. Petty had been content with Ferrone’s contributions and was already embracing a sound that didn’t require Lynch’s style, while Lynch’s dissatisfaction only widened the gap.

The defining moment came when Lynch missed a scheduled gig at The Viper Room in Los Angeles, telling Petty directly that he was “on the East Coast” and wouldn’t play. At first, the band booked Ringo Starr as a substitute — a high-profile fill-in that seemed to declare, “We can still make this work.” But Lynch showed up within 24 hours, seemingly out of pride rather than reconciliation.

It was clear to Petty — and to the band’s management — that the relationship had deteriorated beyond repair. Rather than confront Lynch directly, Petty’s manager Tony Dimitriades delivered the official news: Lynch was fired. In a call Lynch later recalled simply as, “Am I fired?” the curtain closed on one of the most important creative partnerships in the band’s early history.

With Ferrone installed as the Heartbreakers’ new drummer, the group continued to record and tour — but the emotional chemistry that had powered their earlier success had noticeably shifted. The lineup change didn’t break the band entirely — the Heartbreakers remained active and respected — but it did represent the end of the classic version of the group.

Looking back, Petty’s decision reflected both artistic evolution and the inevitable strain that comes with decades of collaboration. What started in the mid-1970s as a tight, democratic band eventually became an engine driven more by Petty’s creative impulses than by collective cohesion. When those impulses no longer meshed with Lynch’s contributions, the friendship and musical partnership could no longer survive.