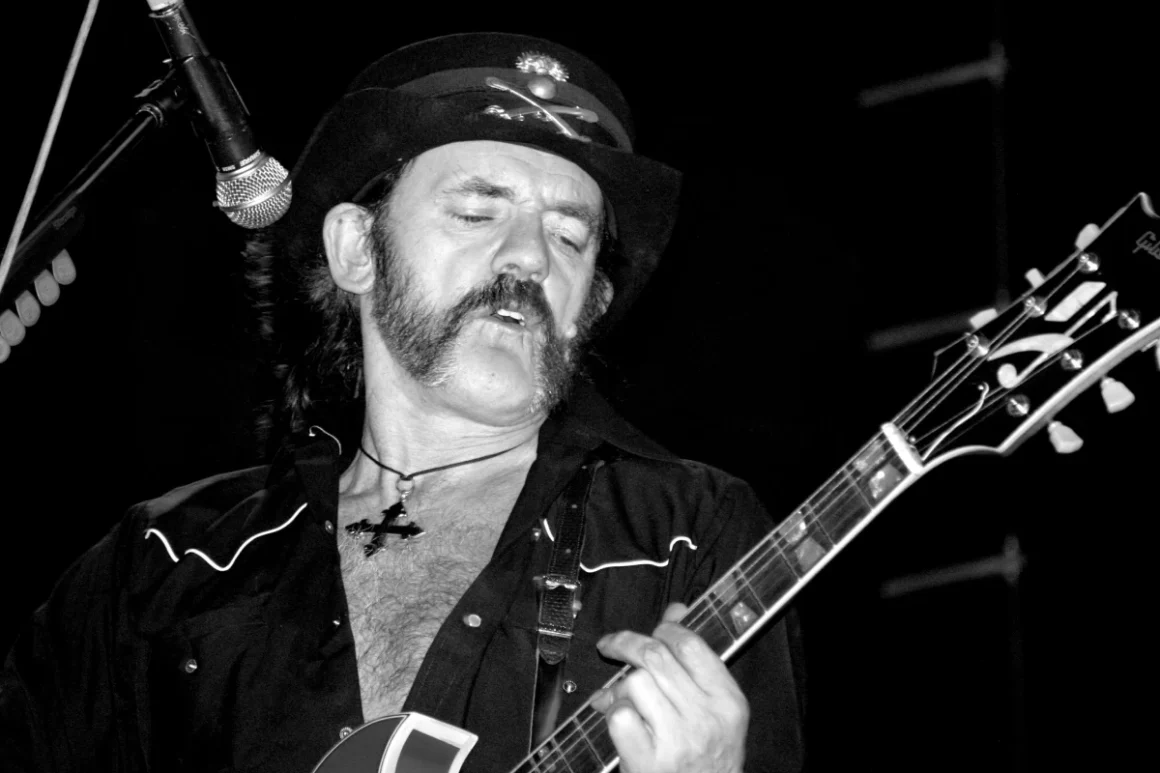

Lemmy Kilmister — the late frontman and bass force behind Motörhead — didn’t just redefine what it meant to play heavy rock bass, he also had strong opinions about who the greatest bassist in history really was. And according to Lemmy, there was one name above all others: John Entwistle of The Who.

Long before Lemmy’s own thunderous Rickenbacker tone became instantly recognizable, he celebrated bass players who commanded their instruments with precision, flair, and creative fearlessness. Among all his peers, Entwistle — frequently nicknamed Thunderfingers — stood out in Lemmy’s mind as the definitive example of what a bass guitarist could be.

“The best bass player on the face of the earth,” Lemmy declared of Entwistle — “He was the best for me, no contest.”

“You never saw him flicker. Never a bum note that I ever heard. And he was so fast, both hands going like hell.”

He even singled out the Who’s classic “My Generation” as a perfect showcase of Entwistle’s skill, noting that even working out the solo is a challenge — “but thinking it up? That was something else.”

Lemmy’s perspective wasn’t shaped by casual admiration; it came from a deep understanding of bass as a driving force, not just a backing rhythm. Throughout his career, Motörhead’s music leaned on that philosophy: bass that punched, cut through the mix, and blazed like a lead instrument rather than sitting quietly in the background.

In Lemmy’s view, Entwistle had a rare combination of power, technical mastery, and consistency — qualities that set him apart even among rock’s elite. Entwistle’s approach was unflinching in both rhythmic strength and melodic invention, a quality Lemmy admired immensely. Not just a low‑end foundation, Entwistle’s work often carried songs with unusual confidence and complexity.

It wasn’t just speed or technical ability that impressed Lemmy; it was a sense of command — a feeling that Entwistle didn’t just play bass, he inhabited it. From blazing solos to deceptively powerful fills, his style was fearless, assertive, and unforgettable.

While Entwistle held the top spot in his estimation, Lemmy didn’t ignore other innovators. He once described Paul McCartney as a close second, praising his melodic instincts even while noting a more gentle approach in his playing.

Lemmy also shared respect for bass players across styles — from the fluid pop phrasing of Carol Kaye to the rhythmic inventiveness of Flea and the rock steady groove of Bill Wyman — demonstrating that his appreciation wasn’t narrow, but shaped by the qualities he valued most: rhythm, feel, and personality on the low end.

Lemmy’s own bass style — loud, distorted, and aggressive — became one of rock’s signature sounds. But even as his music helped redefine the instrument’s role in heavy genres, his admiration for Entwistle provides a fascinating glimpse into the mind of one of rock’s most iconoclastic players: a man who knew greatness when he heard it.