Frank Zappa once boldly proclaimed, “Without deviation from the norm, progress is not possible,” a mantra that underscores his perspective on music and culture. The Beatles, often hailed as the epitome of musical innovation, epitomized a kind of progress that Zappa viewed as conformist in its own way.

While they introduced the mainstream to an eclectic mix of artistic expression and studio advancements—giving rise to landmark albums like Revolver—Zappa saw his role as something different. For him, real progress meant swerving far from conventional paths, going so far as to parody The Beatles’ image of peace and love on the cover of his satirical album We’re Only In It For The Money.

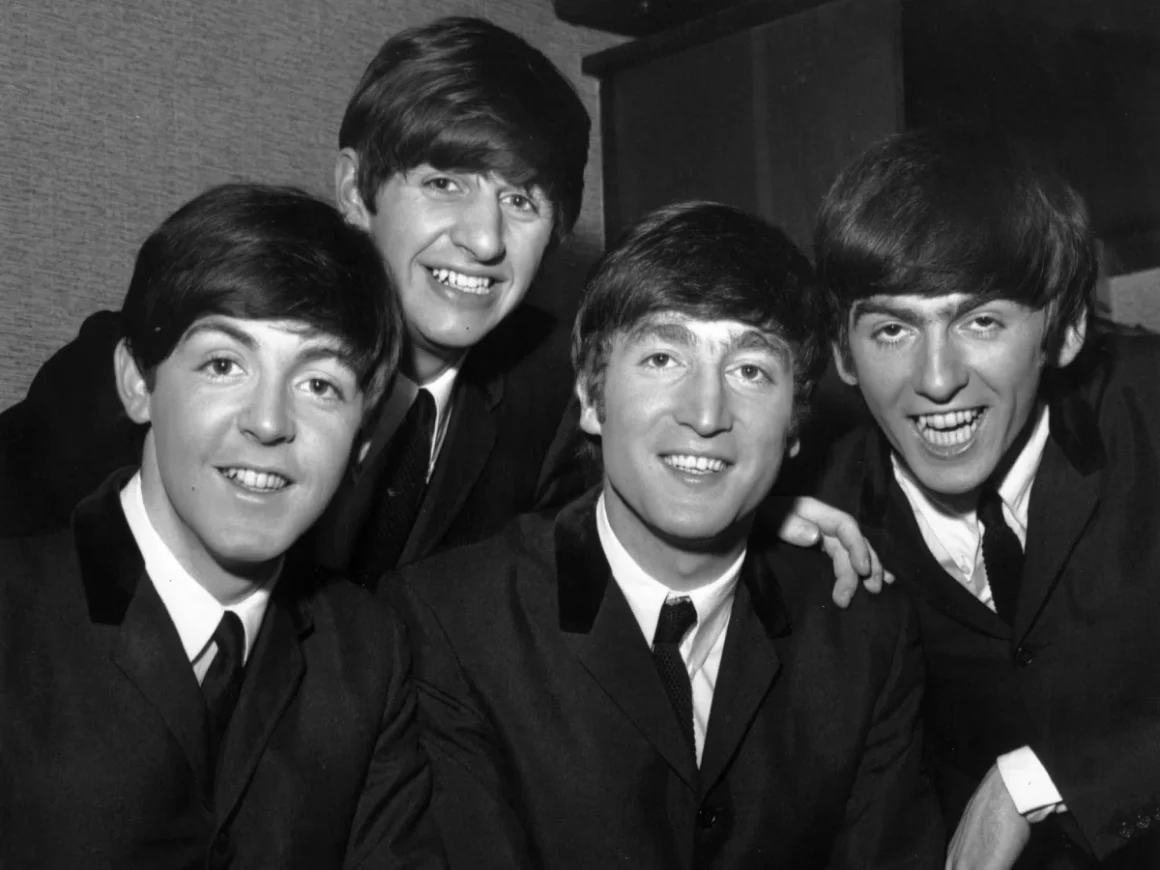

Zappa was never shy about his opinions on the Fab Four. He dismissed their legendary status with statements like, “Everybody else thought they were God! I think that was not correct. They were just a good commercial group.” Zappa, who once worked in advertising, recognized the growing impact of image in the music industry long before many of his contemporaries. In the mid-1960s, he believed that modern music had become half about presentation—a shift The Beatles personified with their iconic looks and evolving personas.

Much of Zappa’s criticism seems to be a mix of genuine opposition and calculated publicity. As his former assistant, Pauline Butcher, later explained, he didn’t play their kind of music, nor did he share the look of “pretty boys” like The Beatles or The Rolling Stones.

Embracing the need for self-promotion, he intentionally crafted his image to stand apart: from unorthodox photoshoots to his wild hair and quirky fashion, Zappa’s persona was engineered to grab attention. His seemingly relentless critique of The Beatles wasn’t just about disdain; it was part of his method to carve out a unique place in the crowded music scene.

Despite his outward disapproval, Zappa couldn’t resist acknowledging The Beatles’ influence. His admiration slipped through on rare occasions, particularly for three Beatles tracks he publicly praised. In 1980, Zappa revealed an unexpected affinity for Magical Mystery Tour’s “I Am the Walrus” during a BBC radio appearance. Following the track, he quipped, “Wasn’t that wonderful?” adding a touch of humor to his praise as he referenced the track’s counterculture message.

Despite his known disdain for drugs and skepticism about the political side of the 1960s counterculture, Zappa’s enjoyment of “I Am the Walrus” was real—albeit laced with his trademark sarcasm. He later covered the song, further cementing his odd admiration for its avant-garde style.

Another Beatles song he respected was “Strawberry Fields Forever,” a groundbreaking piece that pushed sonic boundaries. Even George Martin, the Beatles’ producer, considered it a “modern Debussy,” a comment that no doubt resonated with Zappa’s affinity for blending classical ideas with rock. To Zappa, this song represented a daring experimentation that set it apart from the mainstream work he often criticized.

The third Beatles song that caught Zappa’s attention was “Paperback Writer.” Though a departure from the surrealism of the previous two, this track’s narrative and subtle literary references intrigued him. Zappa once suggested that The Flying Lizards should remake it with their quirky edge, though his suggestion went unheeded.

Ultimately, Zappa’s sporadic appreciation of certain Beatles tracks reflects his complex approach to art and influence. These moments reveal that beneath his public resistance to pop culture lies a nuanced artist capable of extracting value even from sources he found flawed.

His admiration for these tracks wasn’t about surrendering his principles; it was about identifying fragments of artistic quality amid the mainstream—a rare nod from a man known for his unwavering dedication to his own, unusual path.