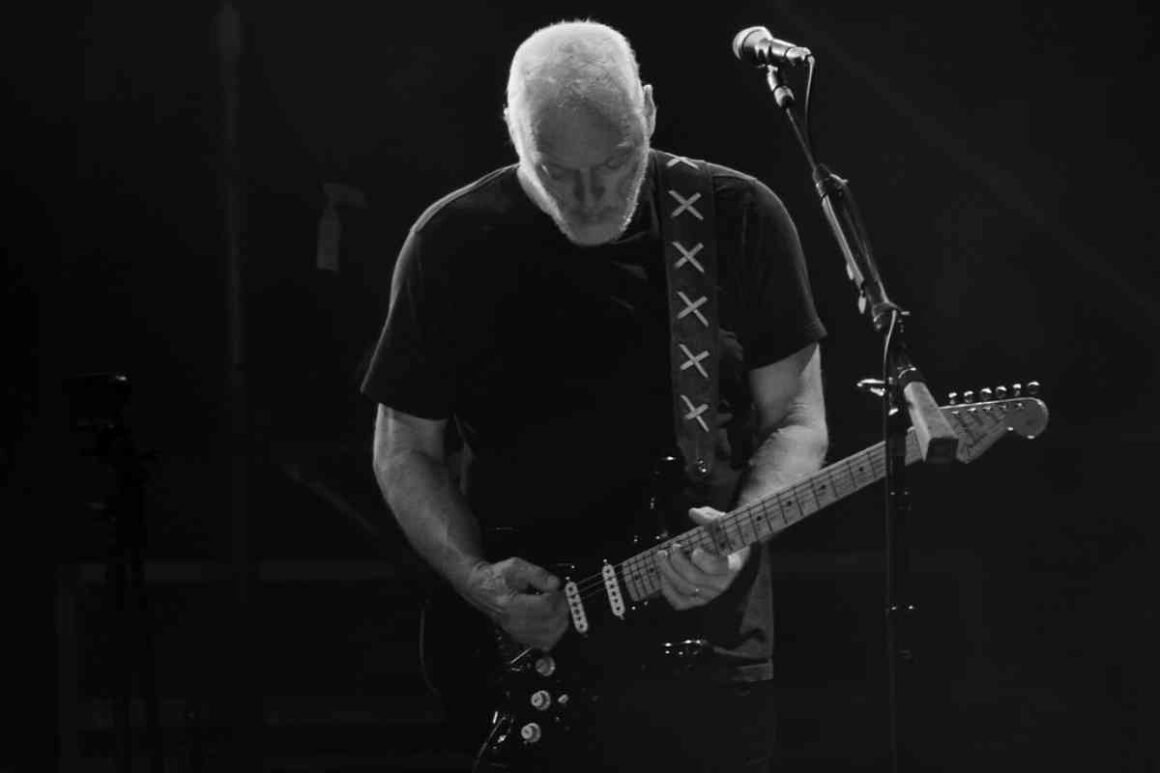

In the world of rock, few bands manage to strike a balance between mainstream superstardom and cult-like devotion quite like Pink Floyd. They weren’t just popular—they were a phenomenon. Albums like The Dark Side of the Moon and The Wall turned them into household names, yet there remains a strange reverence for their earlier, weirder years. But ask David Gilmour, and he’ll tell you plainly: some of that early material is nearly unlistenable.

Emerging in the swirling haze of 1960s counterculture, Pink Floyd began as a psychedelic oddity under the erratic genius of Syd Barrett. With whimsical tracks like “See Emily Play” and “Arnold Layne,” they managed to flirt with the charts while pushing boundaries. But after Barrett’s mental health declined and he was ousted from the band in 1968, Floyd entered a period of sonic limbo—adventurous, yes, but aimless.

Roger Waters stepped in as the group’s primary architect, steering the band through experimental albums like Ummagumma and A Saucerful of Secrets. But that early era, now lionized by Floyd fanatics and acid-drenched record collectors, isn’t fondly remembered by all—especially not by Gilmour, who joined the band just before Barrett’s exit.

Speaking with Goldmine in 1993, Gilmour didn’t mince words. “There are lots of tracks on those early albums, on Saucerful of Secrets and these early singles, which are for real enthusiasts only, if you know what I mean, to put it delicately,” he said. Translation: if you don’t have a Pink Floyd shrine in your basement, you probably won’t make it through Ummagumma.

Gilmour even went a step further: “Certainly, there are tracks that I hate on some of these things.” While he stopped short of naming names, it’s clear the guitarist has little nostalgia for the psychedelic excesses of those pre-Dark Side records. It’s not hard to see why—on A Saucerful of Secrets, Gilmour has just one songwriting credit, buried under Waters, Wright, and even the ghost of Barrett.

It’s impossible to ignore the context here. Gilmour’s long-running feud with Roger Waters adds more fuel to his disdain for this era. These were Waters’ records, shaped by his vision at a time when Gilmour was still finding his place in the band. While fans may romanticize that phase as Floyd’s most creatively unhinged, Gilmour seems to view it as little more than a footnote.

Still, the cult around those early albums persists. Ask any Floyd diehard and you’ll hear impassioned defenses of Ummagumma, More, or A Saucerful of Secrets—albums that defy convention and, arguably, accessibility. And maybe that’s the heart of the Floyd paradox: the band soared to unimaginable heights only after letting go of the very strangeness that built their legend.

For Gilmour, the classics speak for themselves. For the obsessives, the chaos before the calm is where the real magic lies.